WLRN Connects: Stories of Caregivers During The Coronavirus Pandemic

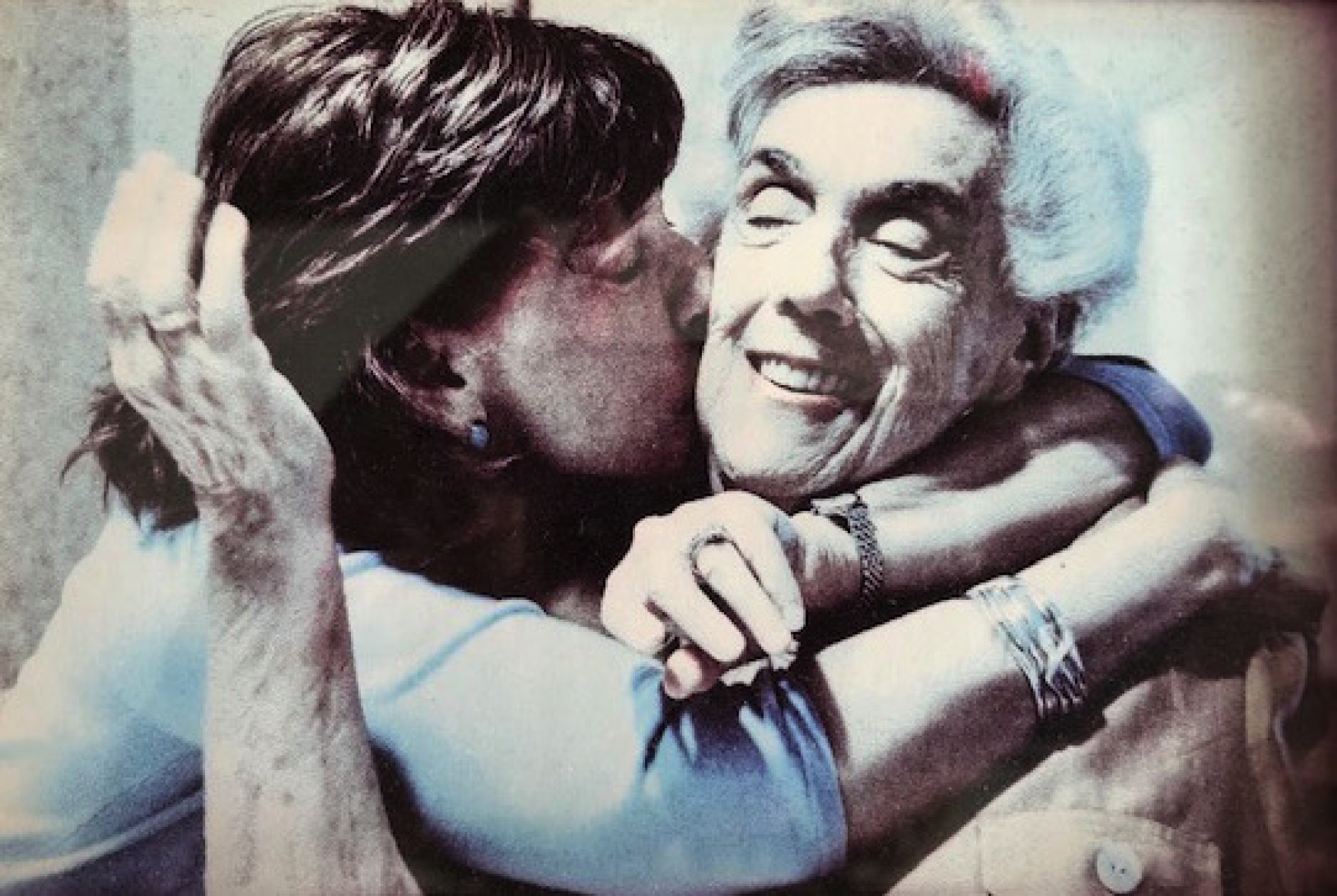

Caring for loved ones who are sick and can’t take care of themselves can be tough. It’s now more difficult because of isolation and economic hardships caused by the pandemic.

Jennifer Mackinday said her life changed in an instant.

In 2005, her brother James suffered severe injuries while serving in Iraq with the U.S. Army—including traumatic brain injury, PTSD, damage to his spine and hearing and vision loss. He was left with lasting disabilities. He was prone to falling. He could walk into traffic without warning. He would forget how to get home.

Jennifer decided to become her brother’s full-time caregiver.

“It’s the best job that I hope no one ever has,” she said. “It’s a privilege to care for a wounded veteran, but I didn’t work in caregiving. I didn’t have a background in health care. That part was a challenge for me, to have to do a complete 180 in my life to be a good caregiver. No matter how much you love somebody, caregiving is really hard.”

Mackinday is one of nearly 3 millions caregivers in Florida, according to a 2019 AARP report. They assume the role when loved ones are unable to take care of themselves.

This responsibility has become more challenging during the coronavirus pandemic. The extended networks that would provide caregivers support are more tenuous under social distancing. Many seniors, who are at greater risk from COVID-19, are facing extended periods of time without physically connecting with their families and friends.

On WLRN Connects, we heard several stories of caregiving during the pandemic. Here are some highlights from the conversation:

COVID and Caregiving

Mackinday said her brother had his 20th surgery in March, when the pandemic began to shut down businesses across Florida. The medical vulnerabilities make him susceptible to the worst of the virus.

During the first few months of the pandemic, Mackinday said she struggled to find basic supplies to care for her brother’s wounds after surgery. Rubbing alcohol and other disinfectants were limited.

Mackinday reached out to her network that she’s cultivated over several years of being a caregiver. They helped her find supplies and discuss best practices for the COVID-19 era.

“I wasn’t comfortable having people come in the home,” she said. “But having a conversation with the folks who are coming in about their protocols, wearing masks, and who they were close to, has made the difference. We’ve been safe so far.”

That support system has also been crucial for dealing with the emotional toll of caregiving — to combat “burnout” that arises with this work.

“At first, I didn’t ask for or accept help. And I got into a dark place,” said Mackinday, who eventually received some emergency mental health care after speaking with a veteran who knew her family.

Mackinday advises folks in her position to seek out nonprofits—like the Wounded Warrior Project, which helps veterans and active-duty service members—and online support groups.

“Finding that group and communicating with them helps you learn how to voice what’s going on in your house,” she said.

Caregiver Planning

Gary Barg moved back to South Florida to become a caregiver’s caregiver. He had helped his mom care for his dad and grandparents for the past 30 years.

Barg then became the primary caregiver after his mom had a stroke in June. He shares those responsibilities with his brother and sister.

“We’re taking shifts, being with her,” he said. “It’s become another family business that we’re running—the business of caring for mom. You are the CEO of caring for your loved one.”

When a loved one falls ill or suffers a major injury, a caregiver steps in much like a manager would, said Barg, who’s the founder and editor of Today’s Caregiver magazine. It’s a transition from an independent to a dependent lifestyle, and that typically means figuring out insurance options, budgeting for food and other essentials, and managing medical appointments.

Rona Bartelstone, who runs OurAging, an aging issues consulting company, said that long-term care planning has to begin before it’s needed.

“Families must start talking about these issues,” she said. “Because if you don’t, then everybody is in even more chaos when it comes time to provide the care.”

Bartelstone, a care management maven, draws heavily from her personal experience. She’s been a longtime caregiver for two parents, two children with serious illnesses, and for her husband, who also had a stroke.

She said there’s a dearth of financial assistance for caregivers in Florida. Medicare could provide some relief. Patients can ask doctors to prescribe home health care that could be covered. Nonprofits and community-based organizations provide some additional services, as well.

It’s the best job that I hope no one ever has.

Jennifer Mackinday

Youth Caregiving

While many caregivers are older, falling into the “sandwich generation,” some like Sati Eubanks start this work during childhood. Her grandmother had triple bypass heart surgery and suffered from breast cancer.

“It’s normal. I don’t really know it any other way,” the 14-year-old said. “I help her with her medications and housework.”

Eubanks is among hundreds of young caregivers in the area, partnering with the American Association of Caregiving Youth in Boca Raton. The group provides them support needed to balance the difficulties of adolescence and caregiver duties.

Dianne Cuco, 19, said the group helped her when she was in ninth grade. With help from her sisters, she’s been caring for her mom who has leukemia. The experience was stressful, and growing up, she said she dealt with depression.

“I got to see these kids that were also going through the same thing,” she said. “I honestly thought that I was alone.”

Cuco said she’s enrolling at Palm Beach State College after recently graduating high school. She hopes to become an ultrasound technician.

Source: WLRN By: Alexander Gonzalez and Tom Hudson

Support families fighting financial toxicity of cancer – here